The Wonder Years

I Was an Early Fundraiser for Kamala Harris. Barack Obama Changed My Life. I’ve Helped Launch and Lead Liberal-leaning Institutions. Why Do I Find Myself Politically Adrift?

“You only leave Google once,” said one of my mentors in the late 2000s.

He was right. It made no rational sense; indeed, a simple pros versus cons spreadsheet would have talked some sense into me. After all, I was now married - and we had a baby on the way! Stability mattered.

“Stay, Rishi.”

I was “somebody” at Google, too: my first job at the company in early ’06 had been to serve as a speechwriter for then Chairman and CEO Eric Schmidt.

But six months earlier, I’d been swept away and there was no turning back: swept away by the election and inauguration of Barack Obama and the prospect of participating in bottoms-up change in an era with a leader who understood the power of social entrepreneurship, and the changemaker in all of us.

I did leave Google. And my wife and I moved to Detroit, where she’s from, in 2010 to found Michigan Corps, an online civic action platform inspired by President John F. Kennedy’s founding of the Peace Corps in Ann Arbor exactly fifty years earlier. “Ask what you can do for your state,” we said. Within a couple of years, we were featured in The New York Times, interviewed on MSNBC, partnered with the Obama White House, and the State of Michigan, and appeared at the Clinton Global Initiative - standing with former President Clinton, to launch a first-in-the-nation Detroit-based microlending initiative, one which which later expanded to Flint - to celebrate our growing model of grassroots civic engagement. Happily, we felt like little ripples in the wider Obama wave.

Years later, in the mid-2010s, after a stint helping expand Twitter across Asia Pacific, then-lame-duck President Obama inspired me again: after years as an expat, my family and I moved to Chicago in part to reconnect with the Obama movement, where the former President’s emergent Foundation was being built amidst a community which - above all else, it still seemed to me - emphasized the power, and wisdom, of the grassroots over the grasstops. “Yes, we can.”

I proudly attended, standing alone in the back of a cavernous hall just miles from Chicago’s Grant Park, the President’s farewell address on January 10, 2017. It felt like a pilgrimage to pay homage, not just another jam to share on Instagram. Months later, I was invited to and attended the first Obama Foundation Summit and reconnected with fellow social-change-y friends from the prior decade. At the end of 2017, I even joined President Obama’s town hall in New Delhi. Fan boy, much?

In short, as recently as a decade after his first election as President, I remained swept away: I was ecstatic to help shape, but mostly to have been shaped by, the Obama era and its inspired community. I still am.

But looking back at the end of my decade of immersion in all-things Obama, I was also beginning - quietly and in my interior life, mostly - to ask hard questions in light of the political upheavals, and illuminations, of 2016. I assumed we all were. And to me, my quiet introspection didn’t feel edgy in the least - after all, I had for years been drawn to the former President precisely because of his deeply introspective spirit.

Looking back on November 2016, what had he missed, I asked myself? What had I missed? Before harshly assessing other Americans, how might I self-assess - and grow?

And, yes, could this fired-up, ready-to-go movement - in a newly-divided America - revisit what first gave it flight in then-Senator Obama’s July 2004 Boston convention speech: namely, a contemplative, conversational, conscientious kind of progressivism that resisted the temptation to Other … others? “E Pluribus Unum,” President Obama would say. “Out of many, one.”

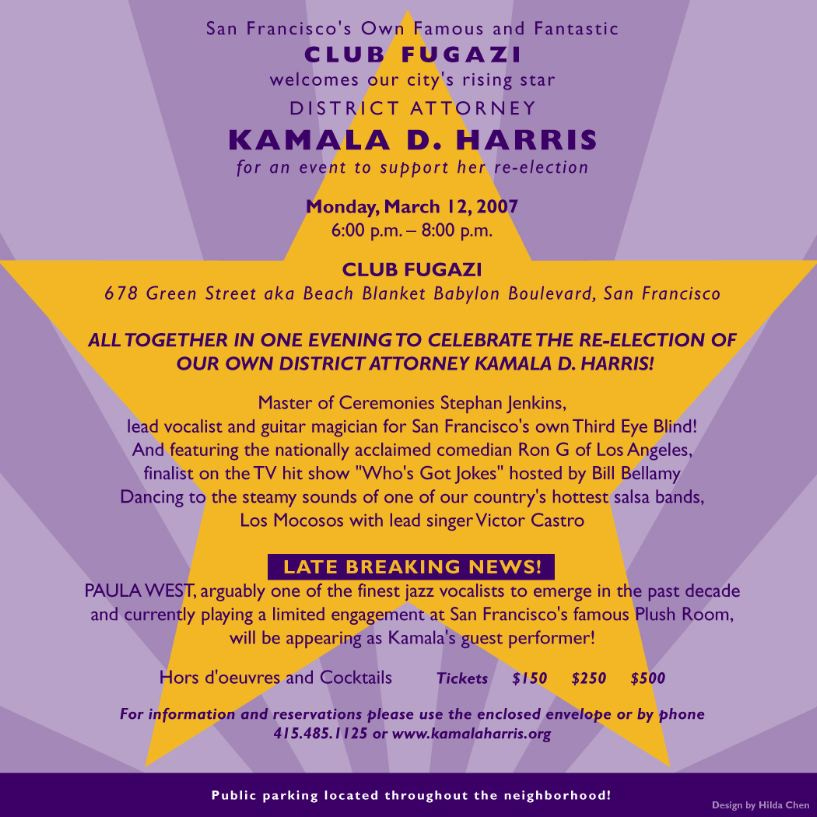

More than three years before leaving Google to found Michigan Corps in 2010 - while I was still at the start of my stint in Silicon Valley - I found myself one spring evening at San Francisco’s Club Fugazi, helping host a fundraiser for the city’s then-little-known District Attorney: Kamala Harris.

To be sure, I wasn’t “somebody” - or even a “kinda somebody” - on her campaign but, in 2007, I served on Harris’s Finance Committee, helped organize a couple of events, shared ideas regarding opportunities to upgrade her digital presence, occupied friends’ inboxes with calls to donate to a rising political star and got to learn from key players in California Democratic politics, many of whom have risen significantly in national prominence since, including U.S. Representative Ro Khanna. Whether or not I was memorable, they certainly made an impression on me.

Looking back at that year, I recall, yes, being drawn to Harris’s story - after all, my mother, like hers, was born in the Indian city of Madras. But I mostly recall feeling pulled by the social currency that came from being on her team, and not by big ideas per se.

For 24-year-old Rishi, that, then, was just fine: social media hadn’t yet taken off but e-mailing fellow 20-something friends en masse, in ’07, to RSVP at kamalaharris.com for events at swanky San Francisco lounges had its own cachet, too.

For years, family and friends have said to me, “Rishi, you’re the one that first introduced us to Kamala Harris.”

And sure, it was nice. To have felt like a first mover - then, and for the decade that followed as she rose to the U.S. Senate - and someone who, in my very little neck of the woods, could claim even just some of her pixie dust.

But at the same time, a decade after first volunteering for her, I’d begun to wonder, quietly and on the inside: politics is about more than my feeling of self-worth, right?

Throughout much of my career, which has included stints as an entrepreneur, executive and educator, I’ve found myself happily in the midst of some of our nation’s most prominent Democratic figures. This community has long been my home.

A photograph of a beaming Franklin Roosevelt adorned my dorm room wall at Princeton. Shaking President Bill Clinton’s hand after a speech he delivered in 2000 celebrating the Progressive Era of the early 1900s was and still is a high point. The precious real estate alongside my college yearbook photo pays homage, in part, to Robert F. Kennedy. Serving as a Princeton University Trustee alongside former U.S. Senator Paul Sarbanes furthered my reform-minded orientation. Ralph Nader’s Project 55 is how I found my footing in public interest work. I recall the knot in my stomach the night Senator John Kerry lost the 2004 presidential election, a campaign I phone banked for.

In 2009, I was enthused to help contribute to a Center for American Progress white paper recommending a more active role for the U.S. Department of Education in providing more postsecondary data to high schools. When Andrew Yang told stories from the heartland in his 2020 race for the Democratic nomination, and proposed Universal Basic Income, I was proud, on behalf of the Knight Foundation, to have helped him and his organization, Venture for America, get to know Detroit in 2011. Following cues in the culture I found myself in, I concurred with friends and family in deriding Republican candidates, including Governor Mitt Romney, as “disconnected and dangerous” throughout the 2012 election cycle.

Saying hello to Caroline Kennedy after a 2017 Obama Summit dinner to tell her that her father changed my life is a moment I’ll tell my grandchildren about. That evening, Pete Buttigieg, then the little-known Mayor of South Bend, Indiana, was sitting across the table from me at dinner and we exchanged brief words about Michigan Corps after our group’s icebreakers and pleasantries had concluded. We follow each other on Twitter. And when entrepreneur Jason Palmer challenged President Biden in the 2024 Democratic primaries, and defeated him in American Samoa, I was proud to call Jason a friend thanks in part due to our prior shared service on the board of Village Capital.

I could go on.

But if collecting affiliations and experiences many identify with the American left were a goal, I could pass the test: a native New Yorker who went to public schools in Queens and then the city’s Connecticut suburbs; a vegetarian son of immigrants who’s still never been around a gun; the recipient of a liberal arts degree from the Ivy League; the occupant of many-a-front-row-seat in Silicon Valley; the co-founder or co-creator of several non-profit organizations, including one focused on black male empowerment, in cities like Detroit; a leader of philanthropic work for America’s largest journalism-focused foundation; a former trustee of my alma mater, and a current director of state agencies and national humanities institutions; and, most recently, a faculty member at an inspired public university where I founded a first-in-the-nation effort to grow the relevance of the humanities - yes, the academic humanities - in preparing reflective leaders and stewards for this AI-ascendant era.

Time and time again, the Democratic Party has shaped my sensibilities; I am who I am because of the oldest active political party in the world. If climbing its movement’s ranks were an outright goal, I’d be able to open my own doors. This community has long been my home.

But today, and in recent years, I’ve found myself politically adrift.

After all the inspiration I’ve felt, perspiration I’ve committed and currency I’ve earned in and around progressive communities, I confess to a growing political homelessness.

Why?

For years, I’ve struggled to confront this question, openly and socially, let alone attempt to fashion an answer.

Like many, my best thinking on all manner of life’s most vexing questions sharpens the more I think out loud, traverse with and test my ideas; but outside of those closest to me, the charged, righteous atmosphere of the last decade has presented such few opportunities for wide, candid, learned discourse. How thick is my skin, I’ve wondered, and is politics-by-therapist a thing yet?

I’ve agonized for months: might a longer-form, admittedly-vulnerable written attempt to publicly advance a long-suppressed interior conversation to a wider exterior, however belated, prove cathartic - and constitute the kind of citizenship worthy of the civic-engagement values I’ve long professed to hold dear?

And in our quick-answer, quick-judgment culture - one I’ve perpetuated myself via leadership roles at companies like Twitter - what if the reflections I share from my inner life consist not of the rushed pronouncements we’re all inundated by but instead with… more questions?

Perhaps a helpful place to start is with the words of an architect of one of the Democratic Party’s great institutional legacies: the late Eli Segal, a former aide to President Bill Clinton and the founding leader of the Corporation for National and Community Service, which oversees our nation’s preeminent national service program, AmeriCorps. His national service vision, like that of President Kennedy decades earlier, inspired my own service journey.

One late afternoon in early ’05, my co-workers from College Summit and I gathered in a dimly-lit conference room at the Watergate (the office building, not the infamous hotel) to hear Segal speak to us about the inspiration and perspiration it takes to make lasting change. College Summit, now PeerForward, is itself a special organization where I have crossed paths with - and been inspired by - many who have gone on to build prominent careers in Democratic politics, including Jaime Harrison, PeerForward’s former COO and current Chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

Segal said something that afternoon many of us will never forget:

“The greatest movements are those in which poetry and prose are in stride with one another.”

Heads nodded not just because he seemed right in the abstract, but because Segal’s instincts seemed to be affirmed by our most recent lived and learned experiences.

Yes, maybe it was because we were young, but it did seem self-evident to many of us in the room - in the midst of a turbulent George W. Bush presidency - that for most of the prior century the Democrats were the party of not just inspired chords but intellectual coherence, and curiosity. The party of Roosevelt, the Kennedys and Clinton was soulful - and smart. The two impulses balanced each other; to immerse oneself in Democratic politics was to feel your soul soar, and your curiosity deepen. Right? To be progressive was, almost definitionally, to exude an always-on, cosmopolitan openness to new inspiration and ideas.

And Segal, in my mind at least, wasn’t just referring to the importance of “well-run” movements. I took his passing insight as an allusion to the criticality of mixing political purpose with precision, personality with principles and, yes, poetry with prose. A politician’s platitudes might primarily be designed to evoke base emotions, yes, but any tendencies to wax exclusively poetic on the Democratic side was balanced by an always-on cerebral culture, too, one that also invited in and insisted on the wisdom of all Americans, it seemed to me.

Roosevelt’s “This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny…” and the all-hands-on-deck New Deal. Kennedy’s “Ask what you can do” and the rallying cry of the Peace Corps. Clinton’s “We know there's not a program for every problem,” and the beginnings of AmeriCorps.

Agree or disagree on their particular areas of policy emphasis, the Democrats, I thought, understood the power of political poetry in shaping American self-understanding and identity, yes - but, above all else, they engaged audaciously with the prose behind big American ideas, no matter their point of origin.

And then came Barack Obama.

Wasn’t his singular mix of poetry and prose why we fell for him?

“The President fills the room with charisma, yes, but also with a sense that he’s the smartest person in the room,” a friend of mine who worked in the early Obama White House once told me.

Watching, for instance, the former President interrogate the minutiae of health care policy, in bipartisan town hall after town hall, summit after summit in 2009 and 2010, showcased a Democratic Party culture long built around an endearing embrace of the vitality of ideas - and idea exchange - no matter the message or the messenger.

“I welcome your ideas,” Obama would often say to political opponents. In a nation founded on a sacred idea, that was part of what was captivating.

Beginning 2004, an inspired national conversation we could all be proud of - one grounded in ideas - was itself his central theory of change.

What happened?

If President Obama was heir not just to a party trajectory undergirded by inspiration but to a governing tradition that saw the intellect in everyone, why in the last ten years has it begun to seem to me that the Democratic Party has stopped ascending towards a poetry and prose worthy of posterity - and instead begun descending to a poetry linked almost exclusively to identity and a prose fast losing its spirit of inquiry?

“What’s the best argument against your position?” I try to say as often as I can at our family’s dinner table. “Not just any argument… but the best argument.”

On any number of issues gusting through our nation’s public conversation, the answers aren’t always neat, and no one actor - public or private, individual or institutional - has a monopoly on the right answer. On this much we should be able to agree, right?

Isn’t it, then, essential to ensure our civic tables are chock full of unusual suspects with seating arrangements that spur debate and leaders who open with a poetry that transcends any one tribe and close with a prose that anchors in truths that have withstood strenuous debate? To do so is to lead with a humility grounded in engagement, and not a hubris grounded in expertise; this, it seems to me, is how Democrats led until a decade ago.

In the quiet of my inner life, and on account of perceived vacuums in Democratic leadership, my poetry and prose began to wander. I started to wonder.

I’ve wondered… not to pass judgment, nor because I have clear policy preferences here, but only to channel the sincere inquiry in my heart. It’s the intrinsic value of inquiry - in and of itself - that the Democratic Party taught me to pursue, above all else.

As an example, on social change, I’ve wondered, why have Democrats begun to present as having a monopoly on the intention to make the world a better place? Republicans and independents don’t wake up in the morning seeking to realize a world in which Americans, their allies and marginalized people around the world are worse off and less able to realize their respective dreams, do they?

On speech, I’ve wondered, what should I make of a party that is an heir to civic warmth and wisdom, yes, but also one that has passed scornful judgment on conservative political opponents for decades? Bush, Cheney, McCain, Romney, Ryan, Trump, Pence, Vance - all of these leaders, and more, including many-a-Supreme-Court-appointee, have, at one time or another, assumed the role of polite society’s “disconnected and dangerous villain.” Regrettably, I used to partake in the snark myself.

On race, I’ve wondered, what might Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. make of a Democratic Party whose leaders, past and present, have begun to speak so explicitly - more each passing year, it seems - of voting and governing in terms of race, even as opposing movements grow more racially eclectic?

On affirmative action, I’ve wondered, in an increasingly multi-racial America, aren’t the poorest among us most likely to bring life experiences worthy of the most inclusion?

On social mobility, I’ve wondered, why has the percentage of American children raised without their fathers climbed from 9% to 25% since the launch of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society federal welfare programs?

On immigration, I’ve wondered, what should I make of the fact that the decline of American working-class wages correlates and tracks, strikingly, with the concurrent growth of our nation’s immigrant population after President Johnson’s Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965? What does it mean that this Act, which was the subject of my college senior thesis, is essential to my self-understanding? Without it, my family would not have been able to immigrate to the United States.

On education, I’ve wondered, what should I make of the fact that American educational outcomes, as of President Obama’s second term in office and relative to the rest of the world, have, some argue, declined since the establishment of the U.S. Department of Education in 1979?

On abortion, I’ve wondered, that visceral, protective feeling of fatherhood that took hold inside of me the moment I knew we were pregnant with my daughter, weeks before even first hearing her heartbeat, and eight months before she was born… was that feeling of life invalid? Is there any room to acknowledge this feeling - merely the feeling itself, and just sit with it - in Democratic circles?

On health, I’ve wondered, why have Democrats been so quick to wholly caricature Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a man - as complex as ever, like all of us - who has devoted much of his life to challenging America’s cozy industrial complexes and ensuring America’s children come of age toxin free and mentally well?

On covid, I’ve wondered, even as a triple-vaccinated Obama voter, was all the hate directed at those who dared ask questions about virus origins and ordinances worth it?

On the Supreme Court, I’ve wondered, why is there such dissonance between the Democratic Party’s caricature of conservative justices as “evil” and the observed behavior of these justices once on the Court? On readily-available audio of the Court’s oral arguments, which I listen to as often as I can, I don’t hear evil but, rather, women and men engaged in reasoned, respectful debate with an eye - on issue after issue - of trusting in the wisdom of the American people, and not the whims of nine justices who happen to occupy the bench. No matter how I may feel about them personally, reasonable people could plausibly argue that their legal theory ought to be democratically empowering, and not endangering, couldn’t they? And, regardless, how could a court occupied with the allegedly ever-present danger of Bush-and-Trump appointees reach unanimous 9-0 consensus in nearly a majority of the cases it handles, including many outcomes favorable to progressives?

On politics, I’ve wondered, isn’t a long-term achilles heel for Democrats the rise of a political movement which self-identifies as conservative at a federal level - insofar as it is skeptical of the concentration of distant power - but embraces more progressive approaches to governance the more proximate power is located to the people? After all - notwithstanding our nationalized, digital era - don’t our place-based lives remain primary and shouldn’t localism, in the de Tocqueville sense, remain paramount - and, indeed, central to our uniquely-American signature?

On democracy, I’ve wondered, isn’t the fact we do not live in an outright democracy - but instead, to be more precise, as citizens of an enduring federal republic, one whose aim is in fact to guard us against unpredictable majoritarian impulses and check unhinged power at each step - what we ought to be celebrating as we approach our 250th anniversary as a nation?

On the presidency itself, I wondered, particularly while immersed in Detroit’s philanthropic community as an entrepreneur in the early Obama years, is “federal dollars in, transformation out” the most essential way to view how people and places realize their potential? If progress were so straightforward, might administration by AI be imminent? Or might something more foundational - and human - be at play in the circuitous journey of communities, and a country? Why have Democrats at a federal level begun to sound more like the foundation presidents and venture capitalists I come across professionally - e.g. “we’ll invest in this and that” - and not stewards of a continental-scale republic enabling, rather than presupposing, investments made by those at other levels of government?

On policy, I’ve wondered, as I devour liberal-leaning podcasts and prose, why does it seem to me that - in the main, after the anti-Republican snark - one way to summarize the Democratic policy posture is too often simply the underwhelming notion of… “more”? What are “end points” at which Democrats believe its investments in this or that, or focus on enabling a particular policy outcome, must necessarily stop? Or are there no end points? And by anchoring its movement in always-elusive issue-by-issue end points, have Democrats unbeknownst to themselves ceded, at a federal level at least, the ground on first-principled “starting points” to Republicans? One way to explain the success of Ezra Klein, I think, is his uncommon equal-opportunity curiosity about the prose that lies behind political poetry.

On walking the progressive talk, I’ve wondered, why does Jimmy Carter’s post-presidency - humble, heartfelt and Habitat-for-Humanity-committed - move me more and more with each passing year?

And on courage, I’ve wondered, why don’t we experience, in our center-left media environment, more daring critiques from within - structural critiques, not at the edges - of the Obama and Biden years? If uncritical fanfare for a movement’s leader is the existential threat facing our nation on the other side, as liberals allege, might Democrats find a way to more explicitly be the self-critical change the party seeks in the world?

I’ve wondered about these issues and many more, thanks in no small measure to the critical-thinking spirit of the Democrats I came of age admiring. Had I come of age as a Republican, with a decades-long stake in the party, I’d undoubtedly be reflecting on the coherence and consequences of its movement’s journey.

Most of all, though, I’ve wondered, is there still room to fearlessly wonder inside today’s Democratic Party?

“Mr. Mayor, I wonder, what might a citizenship strategy for the city entail?” I asked rhetorically in a meeting with Detroit Mayor Dave Bing in 2012.

I was trying to illuminate a larger point inspired, in part, by the early Obama years: what if governments across our nation saw it as their duty not merely to problem solve, from above, on each and every issue they confront but to also see each and every citizen across political parties with civic wonder - and, indeed, as a vessel of civic wisdom - whose ideas might be channeled to serve big civic outcomes.

What if we grew the civic table, to include new waves of citizens, and ensured the doors stayed open? It’s this attitude - the Obama poetry of “Yes we can” and the Obama prose of “I welcome your ideas” - that undergirded the work of Knight Foundation, the BMe Community of black men and all else I was honored to help lead in Detroit, including founding Michigan Corps. In my mind, Detroit’s rebound, in recent years, is in no small measure due to its community’s open-source, “everybody-in” attitude in the years immediately following the Great Recession.

This was the hallmark contagious spirit of the early-Obama years, which harkened back to the best of 20th-century Democrats: a feeling that governments, politicians, 501(c)(3)s, foundations, think tanks and other organized instruments of the establishment did not have have a monopoly on good ideas - and that there was untapped, and sometimes disruptive, civic wisdom to be harnessed from the crowd, wisdom that then ought to find its way back into public institutions at all levels. James Surowiecki’s 2004 book, The Wisdom of Crowds, captures some of this essence, too, reminding us that, often, the wisdom of many transcends that of an elite few.

And if “wisdom comes from wonder,” as Socrates said, perhaps the most pressing question to ask then is: what happened, in less than a generation, to the party’s fearless, anything-goes spirit of wonder… a spirit that used to live collectively and in the open.

One answer begins, I think, in April of 2001.

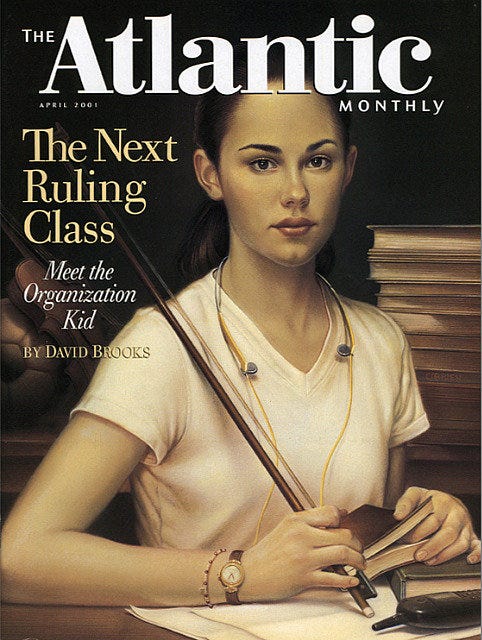

That month and year, I recall sitting in the recently-opened Frist Campus Center at Princeton University, where I was a freshman, reading a viral essay being passed around campus: ”The Organization Kid” by David Brooks, now a columnist for The New York Times. Today, I might encourage Brooks to explore writing a sequel: “The Organization Adult.”

In his essay from ’01, with my alma mater serving as a case-in-point backdrop, Brooks described a generation of future Gen-X and millennial American leaders who had then, while in college, developed a peculiar propensity to trust in authority, please others and orient towards productivity, above all else. While maybe not striking in a vacuum, these tendencies were noteworthy, Brooks argued, when compared to the higher education experiences of prior generations that indexed more heavily on spirits of irreverence and intellectual curiosity. Where had all the authenticity gone?

I felt, rather uncomfortably, that the article described me to a tee. My ambitions, however boldly I cast them then, were fundamentally organizational and institutional in nature: that is, they amounted to dreams of climbing ranks, minimizing contention and, naturally, living life in 30-or- 60-minute increments of productivity. Such was already the life of this older millennial; I finished reading Brooks’ article and, at the heavy, haughty age of 18, moved on to my next “appointment.” Ha.

In fact, such was our state of affairs, that I recall working with classmates to organize an “Intellectual Week” on our campus in 2003 or thereabouts - a daring call to action for otherwise pre-professional undergraduates to, gulp, invite professors to lunch, engage in spirited debate and change the topic from whether we’re headed out that night or not. In retrospect, I cringe, yes, but smile, too; after all, it was college.

But, today, I wonder: are we all now Organization Adults?

All political movements share sensibilities, of course, but I wonder if the shared sensibility that has descended upon the Democratic Party’s coalition in the last decade or so has also ushered in a peculiar kind of speech culture, one that’s “CP” (not “PC”). A Crowd-Pleasing, self-censoring, Organization-Kid persona that predated, presaged and then was pushed ahead by the performative era of social media, all of which coalesced during the later Obama years. I’ve been a part of it, to be sure, but now I wonder, can the groupthink of crowd pleasing be country leading?

Democrats respond, it seems, that the emergency that is President Trump warrants a kind of talking-point unity anchored, primarily, in identity, and not in ideas - the identity of the former President himself, first and foremost, and then that of key liberal constituencies under siege by him.

I reflect back, including from personal experience, and think: haven’t 21st-century liberals lived in a perpetual state of emergency against any-and-all Republicans? And at some point, isn’t engaging with the most compelling messages of an opponent’s movement, and not merely its least compelling messengers, how movements break out of adolescence and into adulthood? Isn’t this the party’s inspired inheritance?

Disengaging from the most wondrous debates of the day and conforming, as some of us Organization Kids did a generation ago, has likely, in part, led to what The Economist reported two weeks ago as the “Trumpification” of American policy: that is to say, while Democrats were resisting and engaging on matters of identity, the contours of our nation’s debates - the big ideas themselves - on issues from immigration and trade to peace and growth are now arguably largely confined to policy spectrums first proposed by President Trump and the Republican Party.

And it’s this, the party’s culture in and around speech, that has me adrift more than anything else.

What if the winners of the future are those who lead communities of people who are devoted to channeling their originality, the permission to go off script - and ponder?

As a former leader of Silicon Valley companies and causes, I had many-an-occasion to be awed firsthand by the long tail that is the passion economy unleashed by the Internet. But I also experienced what the debates in and around free speech look like abroad - and have encountered, firsthand, on my own personal devices, what it feels like to have speech blocked, and platforms censored. As an American, it’s a deep, sinking feeling of loss.

How many of those who advocate for the tightening of our national conversation, given the alleged exigencies Republicans present, have experienced the spirit-breaking feeling of losing access to one’s ability to freely express or access to the voices of one’s fellow citizens? What happened to the profundity of seeing latent wisdom in one’s neighbor - asset-framing, as Trabian Shorters, the inspired founder of BMe, calls it - and Justice Brandeis’s doctrine that the answer to inconvenient speech “is more speech”?

I wonder… can a party atrophying its muscles of confronting compelling opposing ideas long survive, let alone a party over-rotated to assailing an opposing movement’s messengers?

Two-and-a-half years ago, in March 2022, as I was getting to know Virginia Tech, where I’m currently privileged to serve, I attended an event one evening in our Blacksburg campus’s Squires Student Center.

Prominent progressive Cornel West, now an independent candidate for president, who previously challenged President Biden in the 2024 primaries, and prominent conservative Robert George spoke together at a forum entitled: “I See You.”

Moderated in conversation by Dr. Sylvester Johnson, a leading scholar of African American religion, West and George spoke for more than an hour not merely about disagreeing without being disagreeable, but about something deeper: about feeling fondness, and even love, for one another… not in spite of their differences, but because of them.

“I see you.”

I keep the flier of that evening’s event on my office’s wall.

Here at Virginia Tech, where our motto is “That I May Serve,” I felt called the following year to develop a program that draws on the humanities to usher in a world in which a culture of fully - and substantively - seeing others isn’t merely regarded as a cutesy ripple, but a critical requisite for leading civic waves we can be proud of.

I’m asked often by friends and family: why draw on the humanities? And what are they, anyway?

Fortunately, months before the launch of ChatGPT, I had ready a six-word poem I’d written to help express the antidote - indeed, the North Star - our culture sorely needs:

Awe and wonder,

In the other

Again:

Awe and wonder,

In the other

My pitch? The political-and-professional superpower of our era may lie in and around the humanities, and their capacity to cultivate the other-centric skills and sensibilities of storytelling and story listening, introspection and imagination.

My dream? An “I-See-You” world in which fearless awe and wonder in the other - past, present and future others - is not merely a fuzzy afterthought, but regarded as the essential building block to growing a kind of human fulfillment that endures.

We live in a culture of mirrors, I often say, self-involved and short-form - a culture undoubtedly now reflected in our politics; how might we usher in a culture of windows, long-form and other-centric?

Looking back on that young, self-involved volunteer for Harris’s 2007 campaign, and the other-oriented change agent empowered later on by the early Obama era, I wonder, in retrospect: were those the tail end of The Wonder Years?

And then, I wonder, what political currents today, however fallible, most embrace the complexity - indeed, the beauty - of Americans who dare to wonder?

Most of all, though, I’ve wondered, is there still room to fearlessly wonder inside today’s Democratic Party? YES. I would love to go line by line through this with you- with wine, food, Peter and Anuja- oh, and Alex. Much to ask, much to share and some true aspirations for what a Democratic Party could do with Rishi Jaitly in the room. Invoking some Obama hope, we are close to the next wave and how great for all if you were to catch it and ride. Miss you and your thoughts. Great, provocative read.